The price of protection

Posted on: 9 February 2026

Four seconds. That is how long it took for a sitting Cabinet minister to forward a restricted government memo to a convicted sex offender. Not hours of deliberation, not the anguish of someone weighing the breach of a fiduciary duty: four seconds, the speed of a conditioned reflex. And in that automatic gesture, repeated dozens of times according to documents released by the US Department of Justice, lies a perfect anatomy of how mutual protection among elites actually operates.

The Epstein affair has returned with force following the DOJ's release of over three million pages of documents, two thousand videos and a hundred and eighty thousand images on 30 January 2026. But the point is no longer Epstein himself, who died in a federal cell in 2019 under circumstances that continue to generate legitimate questions. The point is what these documents reveal about the structural mechanics of power: a system where mutual protection functions as an implicit contract, right up until the moment the cost of maintaining that contract exceeds its benefits.

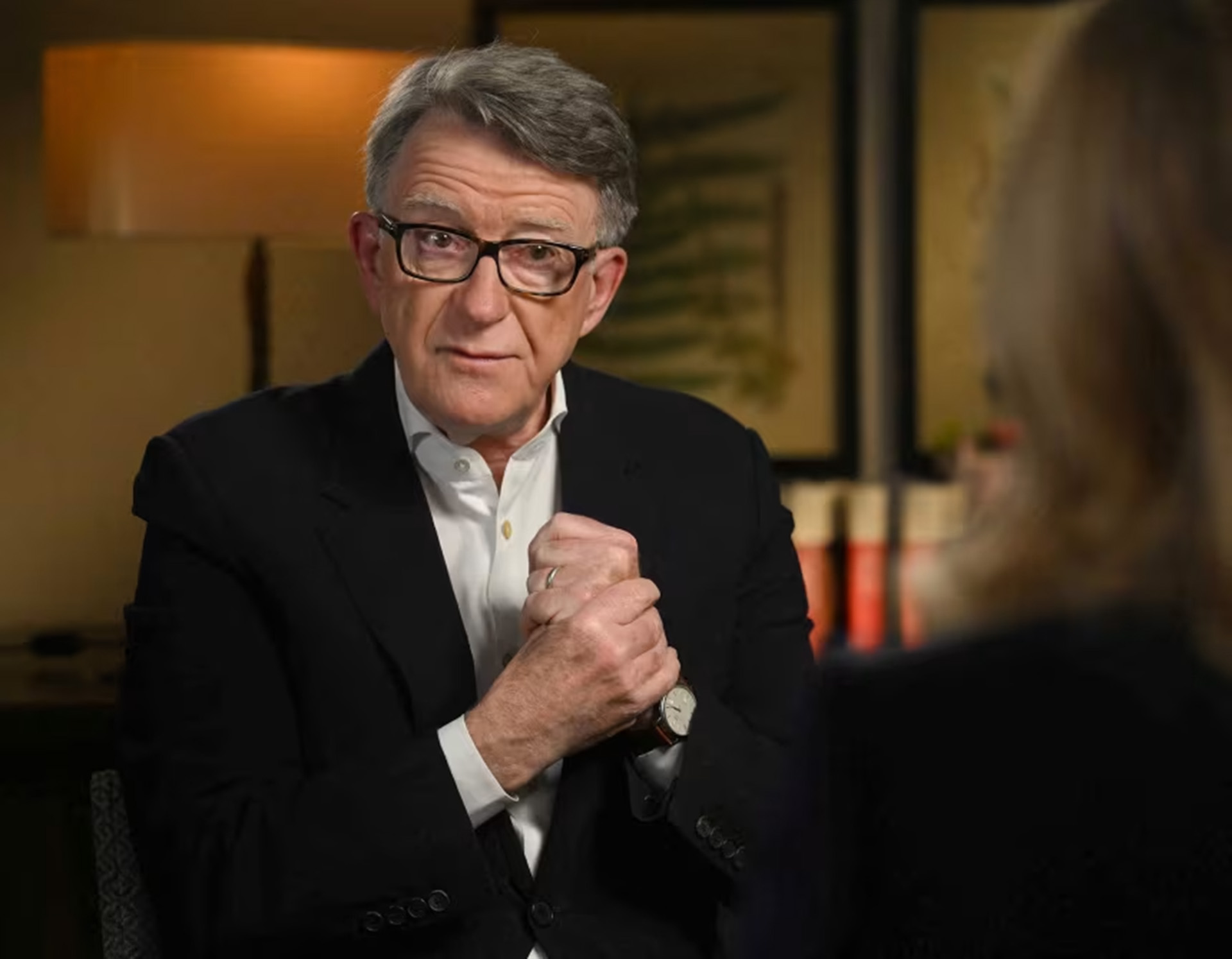

The unfolding crisis provides a textbook case for observing this mechanism in real time. The chronology is instructive. December 2024: despite security services sharing their concerns, the appointment to Washington proceeds. The calculus is clear: a man who understands Trump's world, who commands a network among the wealthy and powerful, who has mastered those political "dark arts" that had made him indispensable since the Blair years. The association with Epstein? An acceptable cost, manageable, containable. September 2025: emails emerge showing encouragement to "fight for early release" after the 2008 conviction. The ambassador is sacked. The cost has become unsustainable. February 2026: new documents reveal that sensitive government information was being passed to Epstein, including a memo proposing twenty billion pounds in public asset sales, and that Epstein was making regular payments to the ambassador and his partner. The Metropolitan Police search two properties. Resignations follow from the party and the Lords.

Each step follows a precise logic, and it is not a moral logic: it is a logic of costs and benefits. The sacking did not come because someone discovered the friendship with a convicted paedophile; that was already known. It came when the political price of maintaining protection exceeded the value of the diplomatic network. The same calculus applies to the stripping of a royal title last October: not when the accusations first emerged, but when the email exchanges became impossible to publicly ignore. When asked about the matter in public, the response from the Palace has been silence, broken only by a single remark about "remembering the victims"; the bare minimum required to signal awareness without admitting anything.

This mechanism is as old as organised power, and it repeats with a regularity that should give pause to anyone still thinking in terms of heroes and villains. It works like this: an individual accumulates relational capital by rendering services to powerful people. Those services create bonds of reciprocity that function as implicit insurance policies. As long as the value of future services outweighs the reputational risk of the association, the protection holds. When the risk exceeds the value, the individual is sacrificed and those who sacrifice him present themselves as victims of deception: "we didn't know," "he lied to us," "no one could have imagined."

The script has been followed to the letter: "betrayed our country, our parliament and my party. Lied repeatedly." Yet security services had flagged the problem before the appointment. The Cabinet Office had conducted a review. The friendship with Epstein had been publicly known for years. The point is that the cost of truth, in December 2024, was higher than the benefit: losing that particular asset in Washington meant losing leverage with the Trump administration. In the equation of power, Epstein's victims weighed less than an efficient diplomatic channel.

This is the structural datum worth retaining, beyond the specific scandal. Mutual protection systems among elites do not operate through organised conspiracy: they operate through alignment of incentives. No one needs to order anyone to stay silent; silence is the dominant strategy for every actor as long as costs remain low. There was no need for blackmail on either side: the bond functioned because it was mutually advantageous. One party gained access to government information of financial value. The other gained money and access to an international power network. The victims, within this architecture, are not a moral problem: they are an externality, a cost that none of the principal actors has any interest in internalising.

The 2008 plea bargain in Florida crystallises the pattern. A federal prosecutor negotiated an agreement that allowed Epstein to plead guilty to two state prostitution charges instead of facing federal indictment for trafficking of minors. Thirteen months in a county jail with permission to leave for sixteen hours a day, six days out of seven. Immunity for all co-conspirators, named and unnamed. The FBI had identified dozens of victims, but the investigation was halted before completion. The Department of Justice, in its 2020 review, described the agreement as the product of "poor judgment" without finding corruption. A formula that says everything and nothing: not explicit corruption, but a system in which a financier with powerful lawyers and connections at the top receives treatment that no ordinary defendant would ever get. The system worked exactly as designed; it simply was not designed to protect victims.

The bitterest irony is that the documents themselves, in their release, replicated the pattern. The DOJ published unredacted images of young women, full names of victims who were minors at the time of the abuse, home addresses visible in keyword searches. Lawyers for the victims called the release "the single most egregious violation of victim privacy in one day in United States history." The system that was supposed to deliver justice inflicted further harm on the very people it claimed to protect. Once again, victims as externality.

But something is shifting in the mechanics of the system, and this may be the most significant aspect for anyone observing structural dynamics. The Epstein case is producing real consequences across a geography of power that spans continents and institutions. A criminal investigation for misconduct in public office, a charge carrying a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. A royal stripped of all titles. The Crown Princess of Norway issuing a public apology. Slovakia's national security adviser resigning. A charitable foundation shut down. A prime minister in the most fragile political position of his tenure, with members of his own party calling for his departure.

What has changed? Not the morality of the powerful, certainly. What has changed is the cost of protection. Three million pages of digital documents, released publicly, searchable by anyone, analysable by investigative journalists with tools that did not exist in 2008. A tax attorney reconstructing a decade of email exchanges in a matter of days. CBS News analysing surveillance video logs from the jail and finding inconsistencies with official statements. Forced transparency has radically altered the cost-benefit equation of protection. Not because the powerful have become more ethical, but because the price of silence has become unsustainable.

This is a dynamic observable across many contexts where information technology modifies existing power structures. The Panama Papers, the Pandora Papers, WikiLeaks: every wave of forced transparency produces the same pattern. First, denial. Second, minimisation. Third, selective sacrifice of the most exposed elements. Fourth, promises of reform. Fifth, reconstruction of the system with updated protections. The cycle repeats because the underlying incentive does not change: those who hold power have an interest in protecting it, and mutual protection remains the most efficient strategy as long as costs stay below a certain threshold.

The lesson, for anyone making decisions in complex environments, is not moral: it is structural. Every system of mutual protection has a breaking point, and that point is reached ever more quickly in an information environment where secrets have a decreasing half-life. The calculation made in December 2024, appointing a known associate of Epstein despite the warning signs, was probably rational given the information available and the expected time horizon. But it was fragile in the technical sense: exposed to a single high-intensity event capable of rendering the entire position unsustainable. That event arrived in the form of three million pages, and the protection system collapsed within weeks.

There is a particular irony in the fact that Britain's most celebrated practitioner of political narrative construction has been brought down by the gap between narrative and documented reality. For decades, the art of spin meant controlling what the public knew and when they knew it. The Epstein files represent the terminal failure of that model. In an era of forced transparency, the question is no longer whether information will surface, but when. And when it surfaces, the cost is not proportional to the gravity of the original act; it is proportional to the distance between the public narrative and the documented truth. The fall came not because of the friendship with a sex offender: it came because for years the friendship was described as barely an acquaintance, while the documents showed an intimate, financial, operational relationship. The lie amplified the damage exponentially. It is a lesson that extends well beyond this particular case, for anyone who must manage the relationship between reputation and reality in a world where the distance between the two shrinks every day.