The surgical window

Posted on: 18 November 2025

There's a paradox I've watched repeat itself across completely different sectors over the past forty years. A company that's "doing well", with stable profits, proven processes and competent management, suddenly finds itself on the edge of collapse within eighteen months. And everyone asks: how could this happen so quickly?

The answer is simple and uncomfortable: it didn't happen quickly. It happened slowly, predictably, whilst every rational decision accelerated the decline.

The invisible mechanism of accumulated fragility

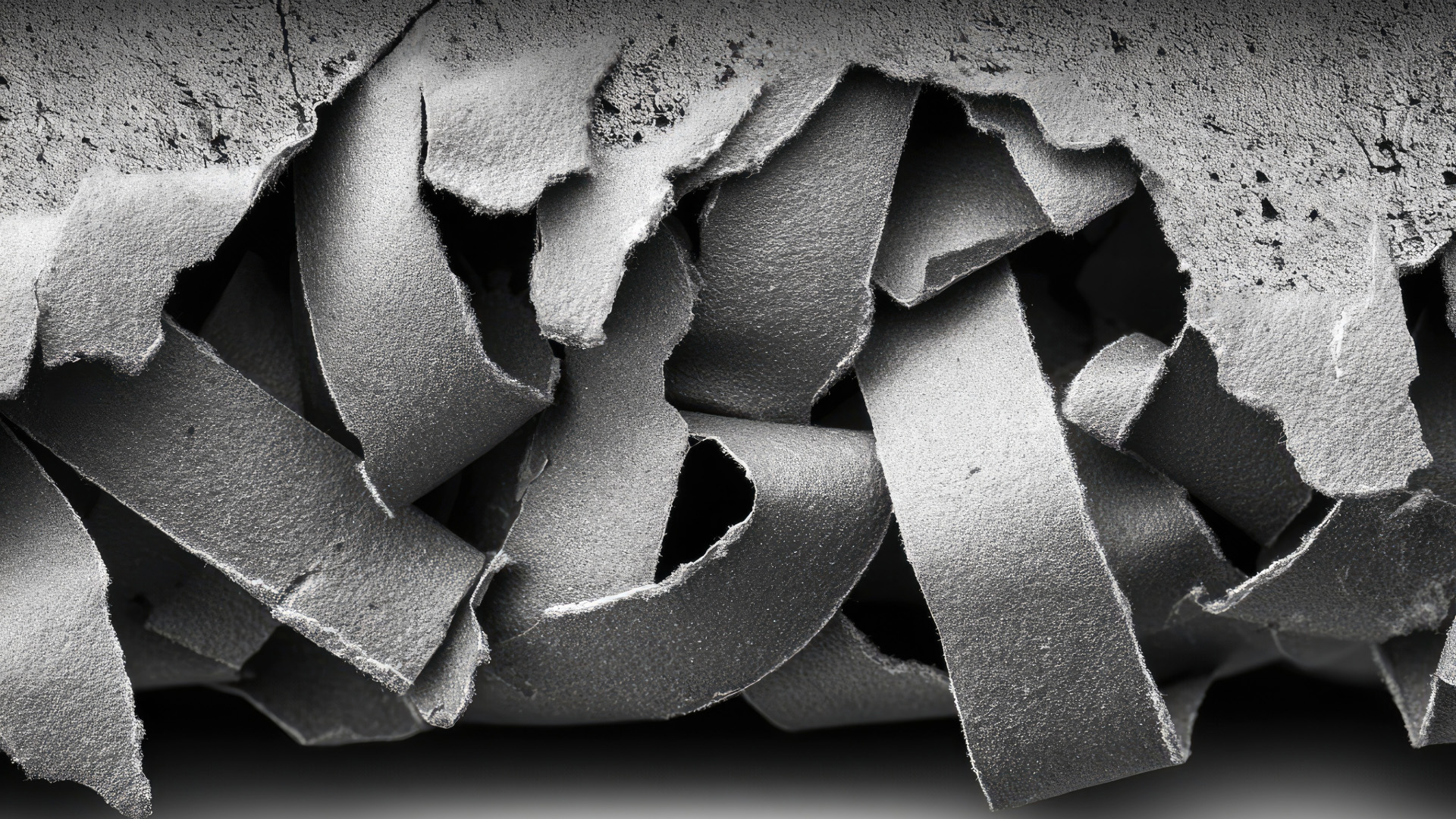

When I was managing the digital transition in the audio and cinema sector during the Nineties, I watched this pattern manifest in real time. An installation that was "working perfectly" required increasingly expensive patches. Each patch solved the immediate problem. The client was happy, the technician was a hero, the quarterly accounts held up. But the system became more rigid, more dependent on that specific configuration of patches, less capable of adapting when the next technological change arrived.

It wasn't incompetence. It was the architecture of incentives that made it rational to build fragility.

The technical director optimised for "zero downtime this quarter". The procurement manager optimised for "lowest cost per intervention". Management optimised for "stable margins year on year". Everyone was doing their job perfectly. And together they were building a system that would collapse at the first significant external shock.

This is the pattern I now call "profitable stalemate architecture". An architecture where all actors benefit from maintaining the problem rather than solving it at the root.

The trap of time and commitments

The problem isn't lack of vision. Most senior leadership sees the systemic disease perfectly well. The problem is that institutional architecture makes it irrational to act on that vision.

Imagine you're chief executive. You can see clearly that your core production process will become obsolete within the next five years. You know a radical transformation is needed that will take three years and cause underperformance for two or three quarters. You also know that your share options vest in two years. The board evaluates your performance each quarter against competitors who aren't undertaking painful transformations. Your senior executives have built careers on the current system and will resist. The main investment fund in your capital has an exit horizon of eighteen months.

In this context, undertaking radical surgery isn't brave. It's professional suicide. Continuing with patches isn't cowardice. It's rational optimisation given the system of incentives.

And this is exactly why apparently healthy systems collapse predictably.

The paradox of the surgical window

I've observed this pattern hundreds of times: there exists a very specific time window where radical surgery is possible. Outside that window, it's either too early or too late.

When the organisation is still strong, with solid revenue, high morale and abundant resources, the disease doesn't seem urgent enough to justify the painful intervention. "Why risk it when everything's working?" is the rational question every board will ask.

When the disease becomes obvious to everyone, with declining revenue, talent leaving and competitors advancing, the organisation is too weak to survive the surgery. Resources for change have been consumed by patches. Political capital to force transformation is exhausted. The window has closed.

The optimal window is typically twelve to twenty-four months before the board sees the problem as critical. This is the moment where the disease is diagnosable through sophisticated metrics but the organisation still has the strength for transformation.

The problem is that at precisely that moment, undertaking surgery seems an unnecessary risk to almost all stakeholders.

The three fatal errors that guarantee collapse

After forty years of direct observation, I can tell you with certainty which approaches fail systematically.

The first error is waiting for the situation to become obvious to convince everyone. When everyone sees the problem, the surgical window has already closed. Nokia saw the smartphone change coming. They waited to have "complete consensus" on what to do. When they acted, they were too weak for the necessary transformation. Kodak did the same with digital. Yahoo did it with search. The pattern is identical across sectors and decades.

The second error is attempting "gradual surgery" to reduce risk. Gradual surgery doesn't exist. It's an oxymoron. Either you do systemic intervention or you do more sophisticated patches. Half-surgery produces maximum organisational pain, zero structural benefit and increased fragility. It's like cutting a tumour in half hoping the remaining part will go away on its own.

The third error is hiring a new external chief executive to do the "dirty work". An outside leader without deep institutional knowledge, without accumulated political capital, with unrealistic timeline expectations imposed by the board, has a failure probability above seventy-five percent in the first eighteen months. It's not a question of capability. It's a question of institutional architecture that makes success almost impossible.

The diagnostic protocol that's missing

If I had to give a board a tool they could use tomorrow to assess the real state of the system, I'd ask for five specific metrics.

First: if you removed your most expensive patch today, how long would the organisation survive before operational collapse? If the answer is less than one quarter, fragility is already critical.

Second: the last time you changed a core process, how long did it take from approval to complete implementation? If more than twelve months, organisational antibodies are lethal.

Third: if your main competitor launched a disruptive innovation tomorrow, how long would you need to respond credibly? If more than eighteen months, the system is too rigid.

Fourth: how many of your senior leaders would survive politically the failure of a major initiative? If fewer than forty percent, you don't have political capital for surgery.

Fifth: can you sustain two or three quarters of underperformance without entering crisis mode? If not, the surgical window is closed regardless of diagnosis.

These aren't opinions. They're falsifiable metrics that reveal the structural state of the system.

What emerges when you see the complete pattern

The point isn't that companies lack courage or vision. The point is that standard institutional architecture, with quarterly incentives, investment fund governance and high managerial mobility, makes surgery structurally impossible at the optimal moment.

It's not a moral problem. It's a systemic design problem.

The few organisations that survive radical transformations have one common characteristic: they modified the architecture of incentives before attempting surgery. They created credible commitments to long timelines. They isolated the transformation team from organisational antibodies. They built sufficient resource buffers to survive the recovery phase.

Amazon under Bezos is the clearest example: they created an institutional architecture that permitted multi-year losses in new initiatives whilst the core business financed exploration. It wasn't "vision" in the romantic sense. It was sophisticated systemic design that made it rational to invest for the long term.

The question for any senior leadership isn't "do we have enough courage?" The question is: "does our institutional architecture make it possible to do surgery in the optimal window, or are we building a system that will collapse predictably?"

Because if the answer is the second, all the patches in the world will only serve to make the collapse more expensive when it arrives.