From Pareto to the "Pareto Principle"

Posted on: 16 October 2025

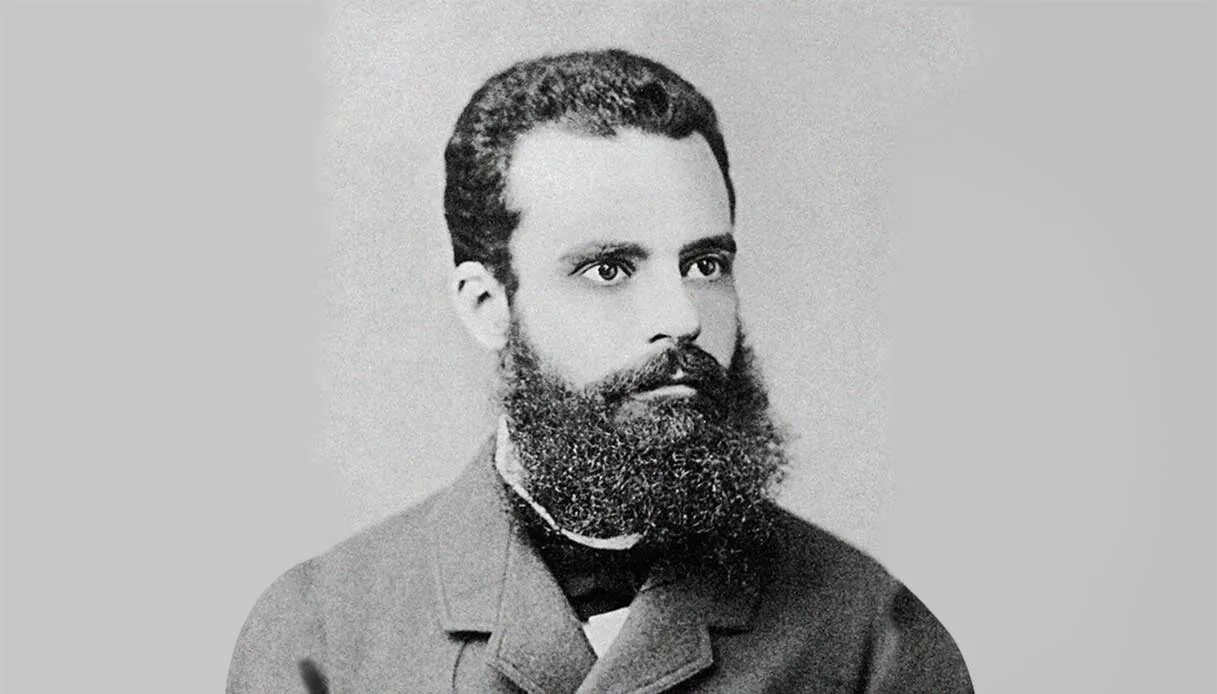

Vilfredo Pareto was a railway engineer who became an economist. In 1896, whilst studying wealth distribution in Italy, he noticed that roughly 80% of the land belonged to 20% of the population. Checking data from other European countries and different eras, he found similar proportions. It was an empirical observation about wealth distribution, part of his broader work on elites and the circulation of social classes.

Pareto wasn't formulating a universal law. He was documenting a recurring phenomenon in wealth distributions, which he later extended to income distributions. His interest was sociological and economic: understanding how inequalities form and persist in societies. He spoke of distribution curves, mathematical coefficients, rigorous statistical analysis. Never, in any of his writings, did he suggest this observation should become a guiding principle for optimisation or management.

So how did we get from Pareto's scientific rigour to the simplistic mantra of "focus on the important 20%"?

The first Leap: from economics to quality management

The first major leap occurred in the 1940s, when Joseph Juran, a quality engineer, stumbled upon Pareto's work. Juran was seeking ways to improve industrial production and noticed that most defects stemmed from a limited number of causes. He christened this observation the "Pareto Principle", even though Pareto had never discussed quality control or industrial production.

It was Juran who coined the expression "vital few and trivial many". This formulation represented a crucial shift: from a descriptive observation about how things are distributed to a prescriptive principle about where to focus attention. Pareto described; Juran prescribed.

But Juran at least maintained methodological rigour. He used statistical analyses to identify causes of defects, collected data, tested hypotheses. The "Pareto Principle" in quality control was an analytical tool, not dogma.

The second leap: From factory floor to General Management

In the 1950s and 60s, the principle migrated from quality control to general management. Business consultants, ever hungry for simple formulae to sell, saw something irresistible in the "Pareto Principle": an apparently scientific rule that promised to simplify complex decisions.

But all rigour was lost in the transfer. Whilst Juran measured defects and identified causes through statistical analysis, the new Pareto evangelists applied the "rule" by intuition. "80% of sales come from 20% of customers" became accepted truth without verification. "80% of results come from 20% of efforts" transformed into justification for cutting everything that seemed non-essential.

No one paused to verify whether the proportions were actually 80/20. No one checked whether that distribution remained stable over time. No one asked whether eliminating the apparent "unproductive 80%" might destabilise the entire system.

The third leap: From eescription to moral imperative

With the advent of personal productivity culture in the 1980s and 90s, the principle underwent one final, definitive mutation. It was no longer merely a managerial tool, but a philosophy of life. Productivity gurus proclaimed: "Identify the 20% of activities that produce 80% of your results and eliminate everything else!"

This pop version of the principle completely ignored Pareto's original context. The Italian economist was describing natural distributions in complex systems, not suggesting they were optimal or desirable. Indeed, much of his work concerned precisely the social problems created by these unequal distributions.

But now the "Pareto Principle" had become a moral imperative: wasting time on the "non-essential 80%" wasn't just inefficient, it was almost immoral. Complexity, redundancy, experimentation, exploration - everything that didn't produce immediate, measurable results - became suspect.

The digital distortion

The digital era has accelerated and amplified this distortion. Social media algorithms, designed to maximise engagement, seem to confirm that only a small percentage of content generates most attention. Analytics data show that few products generate most profits. The "Pareto Principle" appears validated by big data.

But there's a fundamental error: we're confusing observation with optimisation. The fact that distributions tend to skew doesn't mean we should actively eliminate the "long tail". Amazon built its empire precisely by serving the long tail of products that physical shops considered "inefficient" to stock. Netflix revolutionised entertainment by offering niche content that traditional TV would have eliminated according to Pareto logic.

The hidden cost of simplification

The transformation of Pareto's observation into a prescriptive principle has had enormous hidden costs. How many innovations have been stifled because they didn't fit into the "important 20%"? How many systems have become fragile because they were stripped of apparently "inefficient" redundancies? How many organisations have lost adaptive capacity by eliminating everything that didn't produce immediate results?

During my experience in the creative sector's digital transition, I saw companies that had "optimised according to Pareto" find themselves completely unprepared for change. They had eliminated as "non-essential" precisely the diversity of skills and experimentation that later proved crucial for navigating disruption.

Return to origins

Pareto, the engineer-economist, would probably be horrified to see how his empirical observation has been transformed. He studied complex systems with mathematical rigour, trying to understand how they actually worked, not to impose simplistic formulae to "optimise" them.

The real lesson from Pareto isn't "focus on the 20%". It's that complex systems produce complex distributions, often counterintuitive, that require careful study, not pre-packaged formulae. It's that reality is more nuanced than any simple principle can capture.

The next time someone invokes the "Pareto Principle" to justify cuts, simplifications, or extreme focus, it's worth asking: are we observing how the system actually works, or are we imposing a formula that has lost all connection with the original insight of its formulator?

Pareto observed the world as it was, with scientific curiosity and analytical rigour. We've transformed his observation into a prescription for how the world should be. In the process, we've lost both the rigour and the wisdom of the original.